“Unflinching I will face the awful grind of being good.”

It is only to earnest men capable of feeling the inspiration of a great principle that I care to talk, or that I can hope to convince. To them I wish to point out that caution is not wisdom when it involves the ignoring of a great principle.

- Henry George, The Land Question (1881)

The Single Tax v World War One - Part 19

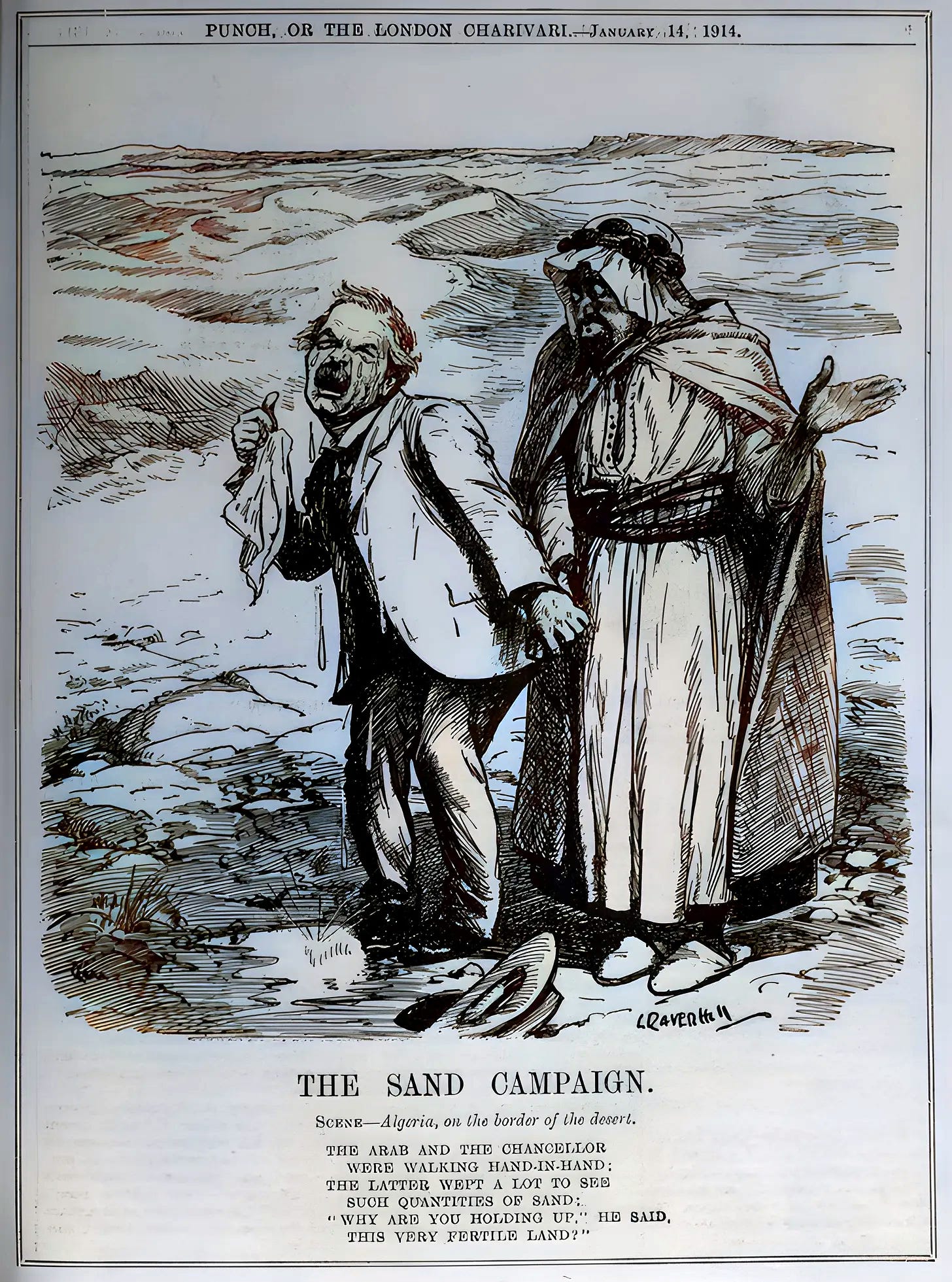

Nineteen Fourteen. As before, it all centred on David Lloyd George. His land campaign was an exhausting multi-front war. So far he had survived, in fact, he had truly slain a dragon. Paths to victory now lay open. In January he went into the Sahara. Four days he remained.

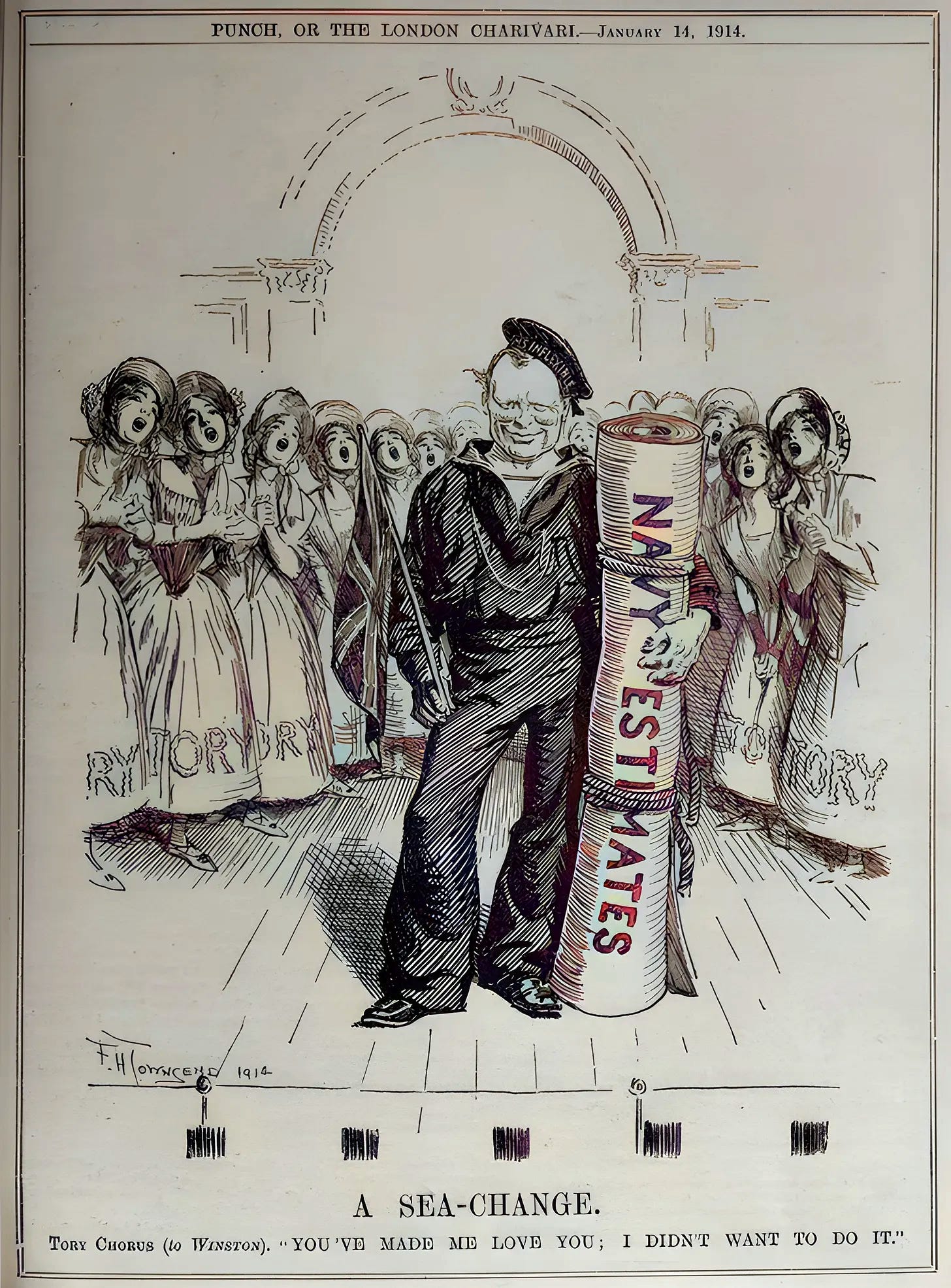

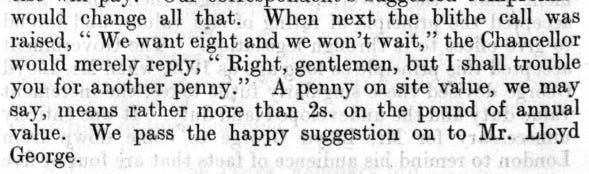

It was the same question again - Dreadnoughts or the Single Tax? In 1914, more perhaps than in 1909, this meant the choice between war and peace. To add to the difficulty, it was his great friend Winston Churchill who wanted the Dreadnoughts. For the Chancellor, the first confrontation of 1914 was with his conscience.

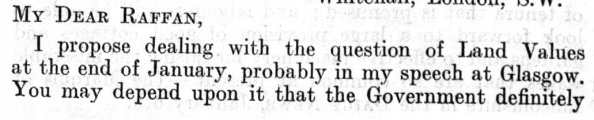

Dear Winston

I have laboured the last few days - not to favour you or to save myself - but to rescue Liberalism from the greatest tragedy which has yet befallen it. I have a deep and abiding attachment for Liberal causes, and for the old Party, and the prospect of wrecking them afflicts me with deep distress.

- David Lloyd George to Winston Churchill, quoted from David and Winston, How a friendship changed history, Robert Lloyd George (2005)

Lloyd George, and many others in the party, opposed Churchill’s massive navy estimates. Was such spending justified? Relations with Germany were, if anything, improving. The government should get back to its domestic reform program. Pressure from the grassroots land campaign was growing. In Scotland in particular, there was loud, aggressive discontent. According to biographer John Grigg, Lloyd George was in danger of losing his position as leader of The Radicals.

On 1st January the Daily Chronicle published an interview with the Chancellor in which

he launched what was both an attack on Churchill’s estimates, and, in effect, a peace initiative

- John Grigg, Lloyd George From Peace to War 1912-1916 (1985)

In the article, he criticised ‘feverish efforts’ to increase Britain’s naval superiority because it would ‘wontonly provoke other nations.’ He further argued that government finance had a role to play in limiting the arms race.

Lloyd George fought Churchill for the entire month of January. Both threatened resignation, Asquith threatened an election. Churchill won … promising to endorse the Land Campaign.

Lloyd George was defending the conviction that Single Tax policy ameliorates international conflict, that the Single Tax movement is both a domestic and an international brotherhood. He was speaking for many party members and back bench MPs. John Grigg reports that there were rumours that Lloyd George was attempting a Radical takeover of the party. The “radicals’ dream of international accord” drove Lloyd George’s new Land Campaign. As we will see below, the Radicals ie the Land Taxers whose voice was Land Values, were demanding the resumption of the revolution and the immediate introduction of land value taxation into the tax system. If the Single Tax really is the root reform, it was time to enact it.

Opposition to the resumption of the land campaign in his own party (which included a group formed specifically to oppose it, called “the cave”) and in the Cabinet is frequently discussed in Land Values. Ian Packer, in Lloyd George, Liberalism and the Land (2001), claims that parliamentary support for the land campaign was strong, it was in fact a welcome unifying force in the party. D.M. Cregier, in ‘Bounder from Wales’, Lloyd George’s career before the First World War (1976) (p229) makes the same point - the pro-reform, anti-war faction was much larger than is commonly assumed.

The next Budget provided an opportunity to advance the program of 1909. Nineteen Fourteen could be the next great step forward towards the taxation of land values.

But Nineteen Fourteen was already in a fever. At least three of the domestic issues the goverment was dealing with - strikes, Irish home rule, and poverty - posed a strategic threat to the country.

The Strikes

As we’ve seen, from 1910 a series of strikes broke out in vital industries - part of the ‘Great Unrest’. The big strikes had not been co-ordinated, but in 1914 workers organised strategically - the coal miners, the railworkers and the transport workers formed a nationwide coalition known as the Triple Alliance. It would be able to stop the country, and it could certainly stop a war.

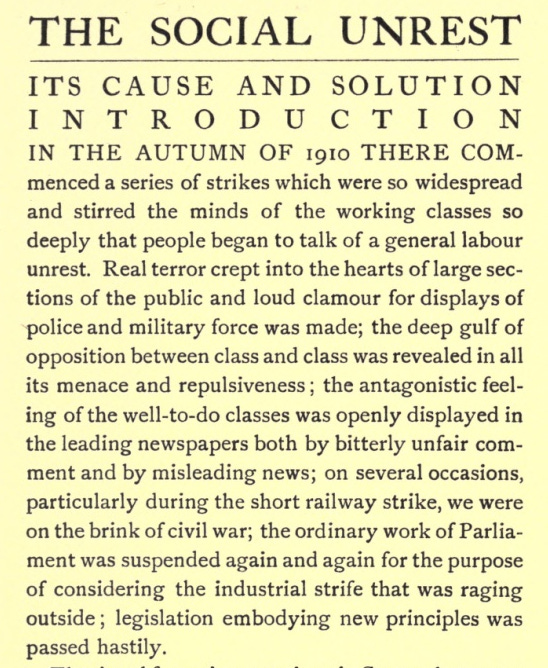

George Dangerfield’s The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935), as previously shown, builds a picture of a country in stages of revolt, succumbing to “nameless energies” that were building in 1914 towards a General Strike “before which that tired General Strike of 1926 pales into insignificance”. The strikes form a major part of Dangerfield’s thesis, they represent one of the great questions Liberalism was failing to answer, but interestingly, he makes it clear that he does not understand them:

Certainly, with the formation of the Triple Alliance, the Trade Unions had discarded once and for all that respectable policy of opportunism which had hitherto hampered them in their dealings with capital. But there was something else in the country — a nameless energy, a new life — which had little to do with trade union leadership. The figures showed that there had been no less than 1,497 separate disputes in the course of the year [1913]; disputes which had started up without reason, suddenly, instinctively, and as suddenly disappeared. What did they mean? How had they come about in a time when employment was expanding and wages, at last, had taken an upward turn ?

It was noticed there that a positive fever of small strikes — so small as to be almost imperceptible — was spreading through the country. Exactly the same thing had happened in 1913. Between January and July [1914] there were no less than 937 strikes. The origins of most of them were extremely obscure, and even unreasonable.

The leaders of the Triple Alliance, urged forward by specific grievances and by that nameless agitation which — to the consternation of the Board of Trade — appeared to be spreading through all the districts of Great Britain, were standing with characteristic reluctance on the edge of a precipice. At the bottom of that precipice lay a General Strike. It remained to be seen whose hand would push them over. By July, 1914, it became very apparent that hands would not be lacking.

One of Dangerfield’s sources, The Social Unrest, Its Cause and Solution (1913), by J Ramsay MacDonald describes an unprecendented crisis in the history of the labour question. The unrest, he claims, was caused by “class conflict”, involving, the “well-to-do”. The book is no Single Tax tract but it is fully versed in the idea of land monopoly as the root source of labour discontent. He acknowledges

and seems to agree with theories which give greater weight to the latter, to Land, as the ultimate root of the problem:

J Ramsay MacDonald, leader of the Labour Party, future Prime Minister. He would make a quickly reversed attempt to introduce Land Value Taxation in 1931.

“To every workman seemed to come a revelation”

Henry George, famously, had just such a revelation. Many have reported a similar experience with these ideas. Land Values was in no doubt that the spread of that revelation, over a period of 30 years, was a key factor in the Great Unrest.

Dangerfield does not discuss the philosophy of the Radical Liberals of this period - the Land Campaign was the personal crusade of a single individual, driven by an archaic class hatred whose origin is biographical.

Had Dangerfield viewed the movement through its own lens, he may have found different answers to some of his questions:

The workers of England, united neither in their politics nor in their grievances, with no single desire for solidarity, yet contrived to project a movement which took a revolutionary course and might have reached a revolutionary conclusion ; and how is this to be explained ?

And he could not possibly have written this about the Liberalism of the period:

The poor, it says, are always with us, and something must certainly be done for them ; not too much, of course, that would never do ; but something.

Lloyd George - “The Country is ripe for Revolution”

- An audience of 8,000 listening to David Lloyd George's opening speech in his Land Campaign, Bedford. 1913: (Banner on rear wall: “The Land for the People”)

Before the new year Lloyd George debated the motion “That this house has no confidence in the Land Policy of His Majesty’s Government” at Oxford University, crowded with future MPs eager to confront the “nasty little Welshman”. They threw a pheasant at him, which hit him in the head. But after hearing his speech, wrote future Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, many then found themselves “delighted, charmed and impressed”. (One biographer remarks that most of these potential future allies, future land reformers, were lost in the war.) Lloyd George did not win the debate but he felt able to say “The Country is ripe for Revolution.” (quoted from D.M. Cregier, in ‘Bounder from Wales’, Lloyd George’s career before the First World War (1976) p218)

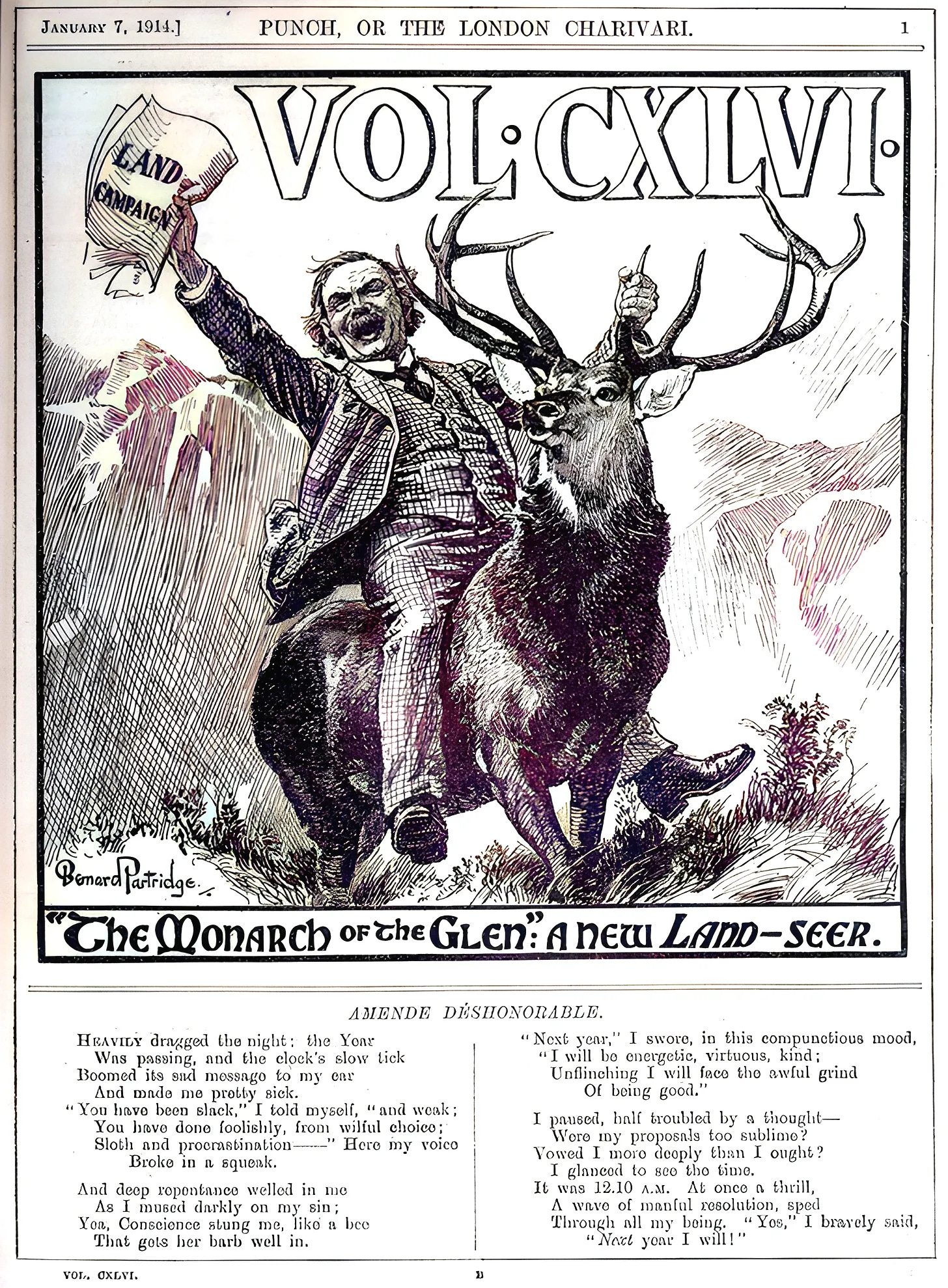

The New Land Seer

AMENDE DISHONORABLE.

HEAVILY dragged the night ; the Year

Was passing, and the clock's slow tick

Boomed its sad message to my ear

And made me pretty sick.

“You have been slack," I told myself, "and weak;

You have done foolishly, from wilful choice;

Sloth and procrastination — " Here my voice

Broke in a squeak.

And deep repentance welled in me

As I mused darkly on my sin ;

Yea, Conscience stung me, like a bee

That gets her barb well in.

“Next year," I swore, in this compunctious mood,

"I will be energetic, virtuous, kind ;

Unflinching I will face the awful grind

Of being good."

I paused, half troubled by a thought —

Were my proposals too sublime?

Vowed I more deeply than I ought?

I glanced to see the time.

It was 12.10 A.M. At once a thrill,

A wave of manful resolution, sped

Through all my being. "Yes," I bravely said,

" Next year I will ! "

- Punch, January 1914

“The year 1914 will be a strenuous one for our supporters, for land is to be the issue.”

“Verily, the issue which we have long looked for and toiled for has come.”

“Time we knew always was on our side, and now events are with us.”

“It is safe to say that Radical electors in every part of Scotland are in the same dissatisfied mood, for there the taxation of land values is accepted as one of the axioms of Radical politics.”

“It is likely to break out into open revolt.”

“If a reactionary Cabinet continues to oppose the demands of democracy there can only be one result - defeat and disaster for the Liberal Party - and that fate will be well deserved.”

Lord Lansdowne: “I deny that there is a monopoly of land”

J S Mill: “The reason why landowners are able to require rent for their land, is that it is a commodity which many want, and which no one can obtain but from them. …

A thing which is limited in quantity, even though its possessors do not act in concert, is still a monopolised article.”

“In twenty-six years public opinion has ripened, revolutions in thought have taken place”

“These are the men who for long years have kept the land question to the front”

“All over the country they are waiting in vast multitudes for the magic word which will draw them into the fight again.”

Alexander Ure: “they crowded to hear him, drawn by one magic phrase - ‘Land Values’.”

“They came for one reason, because they believed land value taxation to be the all-important question.”

“Already far and wide, deep and menacing, the murmurs of revolt are heard.”

(Lloyd George must surely have been asking, would it be wiser to wait one more year? 1915 would bring both a general election and the completion of the national Valuation. If the Liberals won on a Taxation of Land Values platform, the timing would be perfect.)

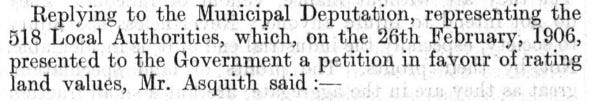

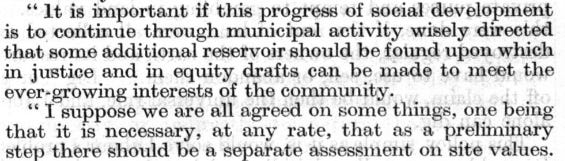

Herbert Asquith, Prime Minister, long time Single Taxer

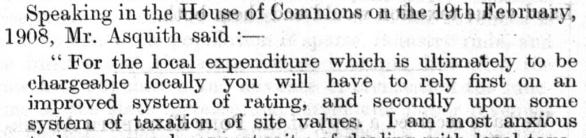

“Human society is not a huge machine, to be controlled and constantly regulated. It is an organism which can only live by the individual life of its parts.”

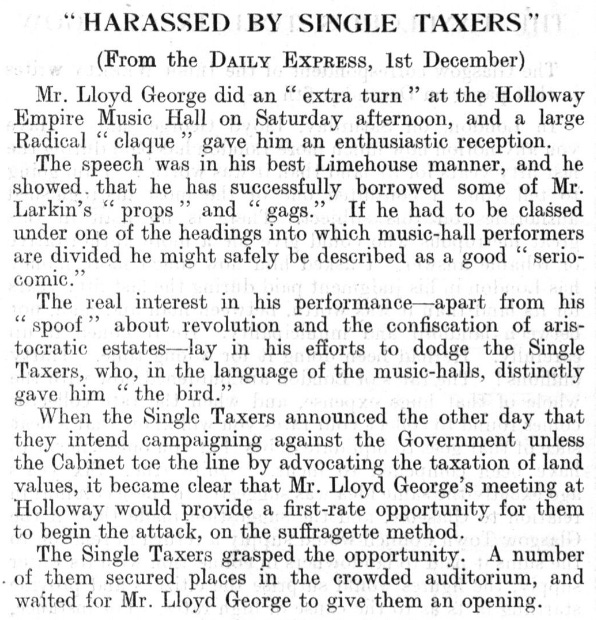

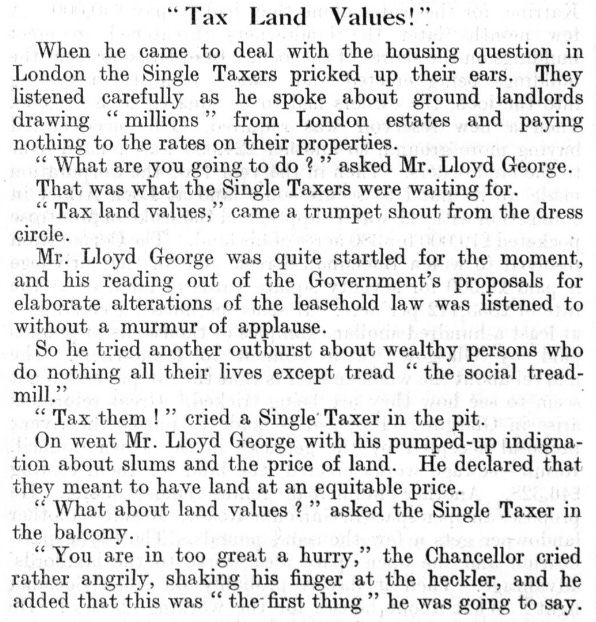

“The real interest in Lloyd George’s performance - apart from his spoof about revolution and the confiscation of aristocratic estates - lay in his efforts to dodge the Single Taxers”

“‘Tax land values’ came the trumpet shout from the dress circle. ‘You are in too great a hurry’, the Chancellor cried”

“In Shoreditch, out of 1,000 boys born into the world under five years, 300 of them are under the sod.”

Rowntree was deeply involved in the new land campaign.

“Clear warning was conveyed to Mr Lloyd George that it is useless for him to come to Glasgow in any guise save that of a Chancellor pledged to the taxation of land values.”

Lloyd George “is now engaged in a great struggle to procure the conversion of his colleauges in the Cabinet.”

“There has been a tendancy to prejudge the Chancellor and his Land Campaign with an impatience for which there is much justification.”

William Reid was the General Secretary of the Yorkshire Land League and an original Glasgow Georgist, having heard Henry George speak there in 1890.

“Mr Lloyd George will come to Glasgow and fight his Land Campaign here the only way he can fight it.”

“British bayonets would bar the way to the land.”

Teddy Roosevelt, Land Taxer.

David Lloyd George: The Reform of British Land-Holding and the Budget of 1914

Bentley B. Gilbert, The Historical Journal, 21 (1978)

This essay is quoted at length because it offers a rare perspective on Lloyd George’s biography.

The land programme has received virtually no attention from Lloyd George's biographers.

Lloyd George's attack on landed privilege had begun with the land-valuation and land-tax provisions of the famous 1909 Budget and were elaborated in the Limehouse speech of I4 July I909.

The House of Lords' intervention on the budget issue, the general elections of 1910 and the Parliament Bill, not to mention Lloyd George's own preoccupation with National Health Insurance, put off the second installment of land reform for three years. ... His goals, a complete and essentially open-ended rebuilding of Britain's rural and urban land tenure, housing, and wage systems, coupled with a basic reconstruction of local authority financial and welfare powers, are so far almost entirely unexplored.

In the spring of I9I2, Lloyd George was restless and unhappy and, as in I908, the Liberals were in the doldrums. After tremendous exertions of the previous three years, the party's political momentum appeared again to have died.

“The fall of the House of Lords was not merely a political event; it was the beginning of a new economic order.”

'At the moment the Chancellor's future career hangs in the air', wrote H. W. Massingham… ‘He is almost completely detached' and is surely about to begin a new phase of his political life. 'Is the budget of I909 to have the sequel which his author designed?' he asked. .. . ‘The fall of the House of Lords was not merely a political event; it was the beginning of a new economic order.'

Between the summer of 1912 and the summer of 1914, while the British political world seethed over Marconi, the National Health Insurance doctors' revolts, Home Rule, and the cost of oil-fired battleships, the chancellor of the exchequer, David Lloyd George, himself a centre of controversy, began to put together a legislative project to reconstruct the system of British land holding. He saw land reform as the major effort of his political career.

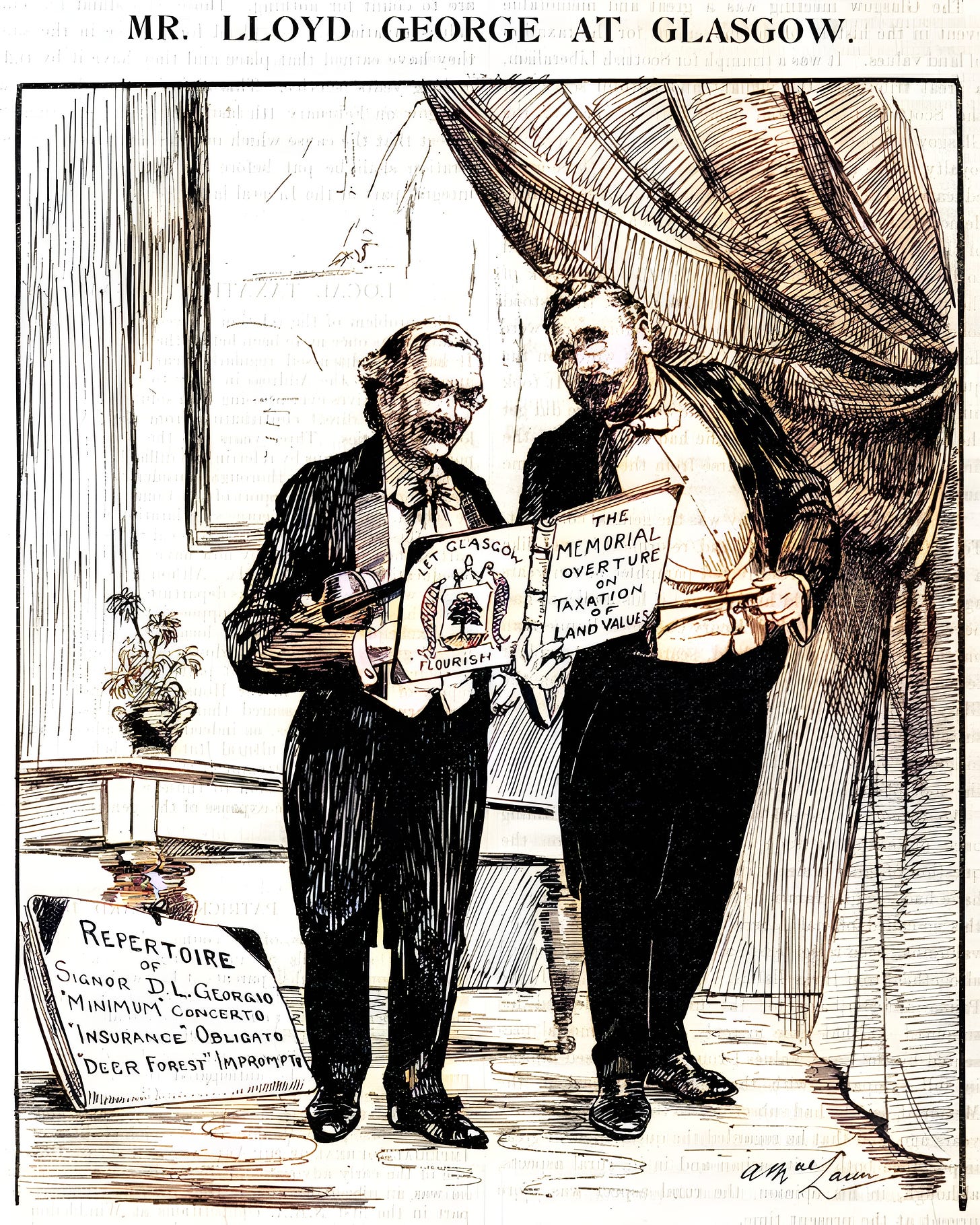

Glasgow

Gilbert, having argued for the importance of the land campaign to Lloyd George, is nevertheless careful not to elevate its importance in history:

The need to do something for the cities and the need for haste, which were clear enough not even to merit discussion, rather than any pressure from the United Committee for the Taxation of Land Values, account for the dramatic change in strategy in the land campaign that occurred at the end of 1913 and for Lloyd George's ill-considered and hasty insertion of site value rating and relief of improvements on the 1914 Budget. The public announcement of site rating came on 4 February I9I4 in Glasgow.

To assess this, see below.

Recap of the recent course of the Land Campaign:

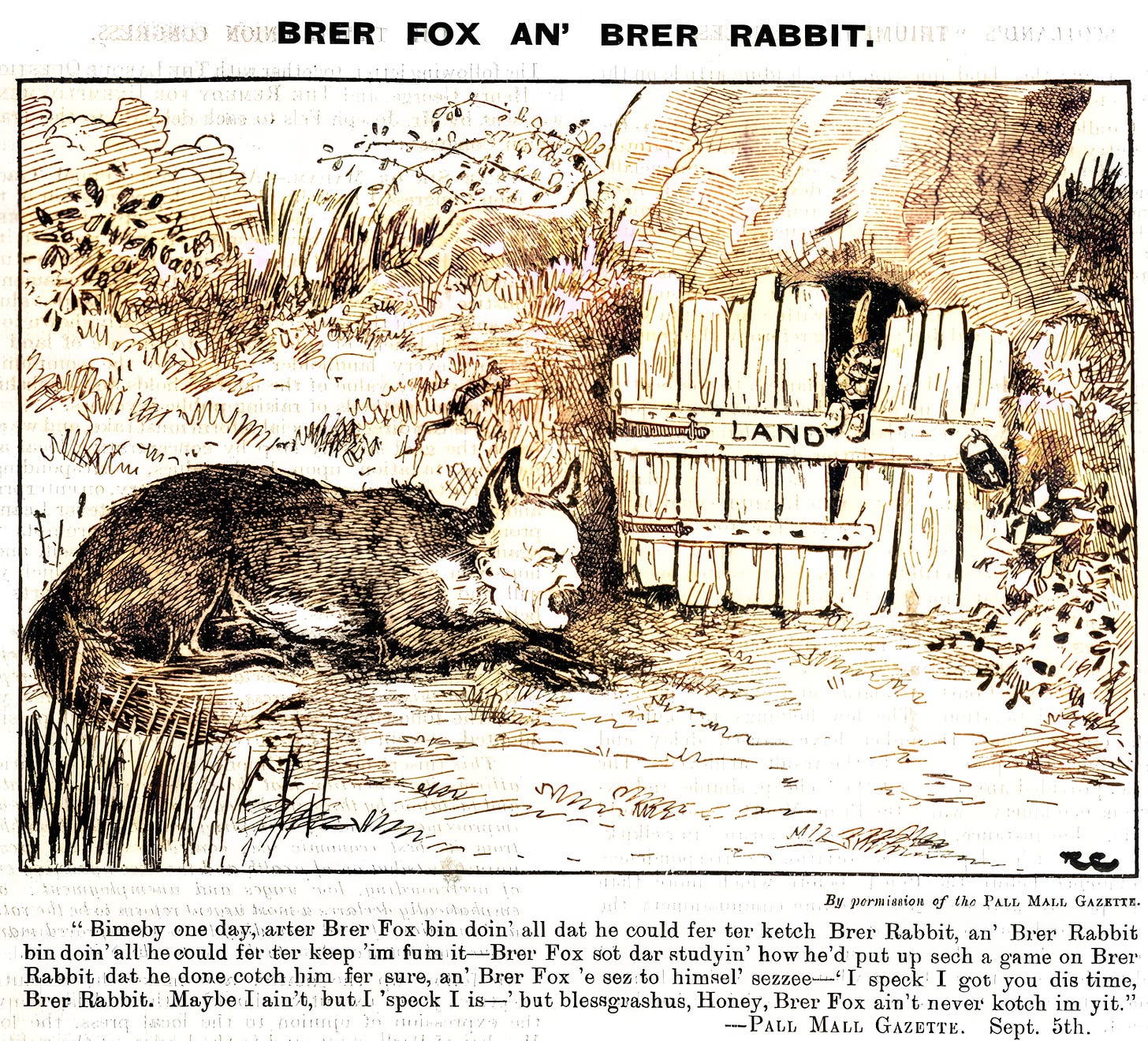

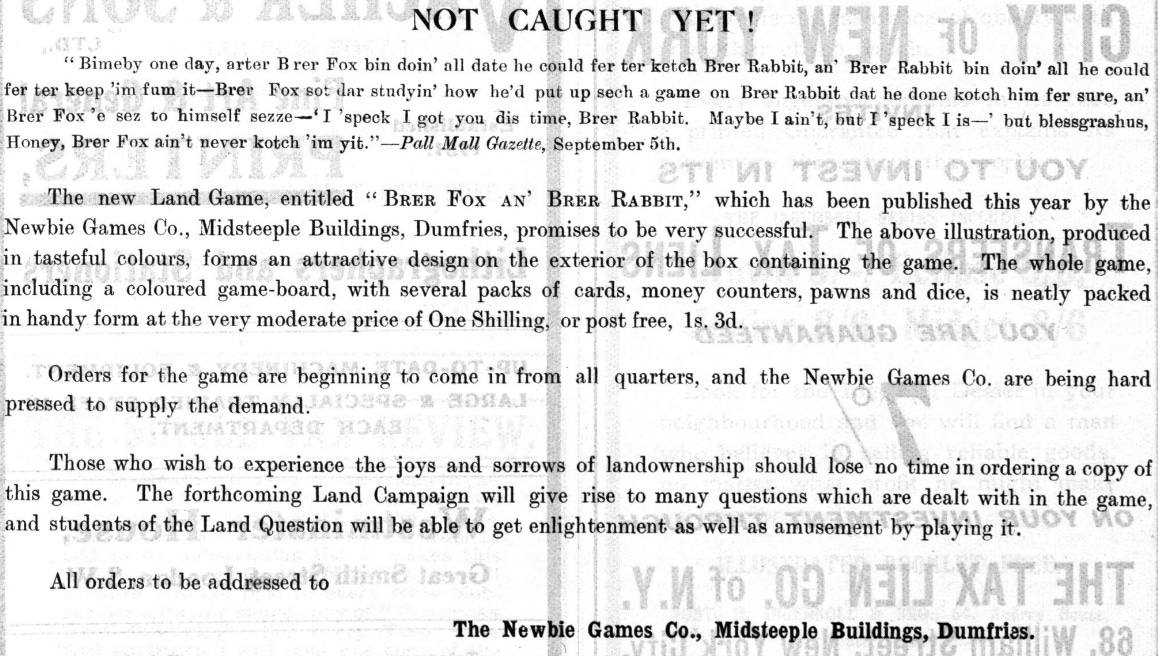

“The land bursting campaign”

The Chamberlain paradox

“The contrast between the one Mr Chamberlain and the other is one of the most amazing phenomena in the history of British politics.”

“No economic gospel of the day is progressing faster than the doctrine rather unfortunately named the Single Tax”

Germany

January 1914: The Liberal Government re-declares the Land War.

Tolstoi: Slavery and poverty are legal phenomena

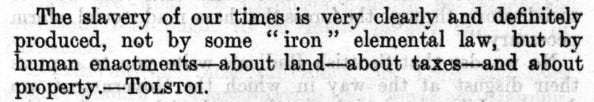

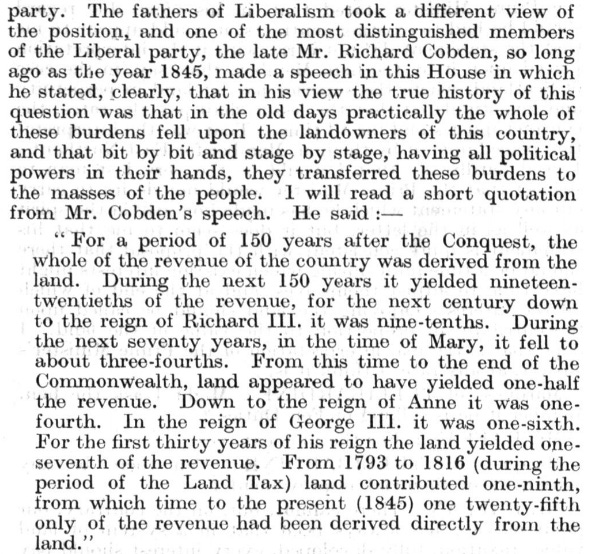

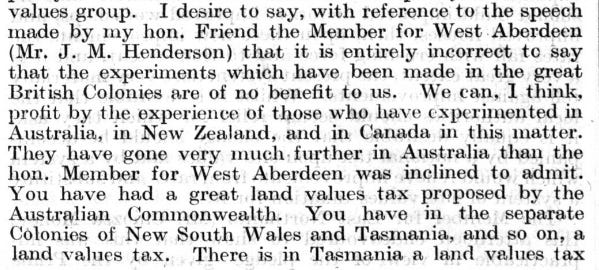

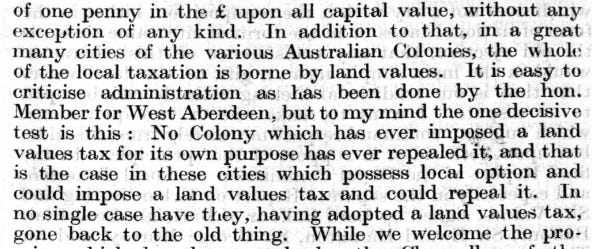

The next 23 snips give a history of Georgist tax reform in Britain’s Parliament. Much of it has been mentioned previously in this series.

New York 1886

The death of Joseph Fels - “the greatest blow the movement has received since the death of Henry George”

The Scottish League for the Taxation of Land Values charged with impatience. Land Values counters.

“Those who stand for land values taxation do not plead for a place in the sun; they have earned that place and they have it by right of long years’ service.”

Lloyd George’s Glasgow speech:

“I really am not a shirker”

“I can assure you we mean to make use of that valuation. I cannot imagine there being any doubt in anybody’s mind on that subject.”

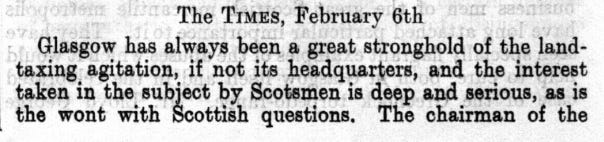

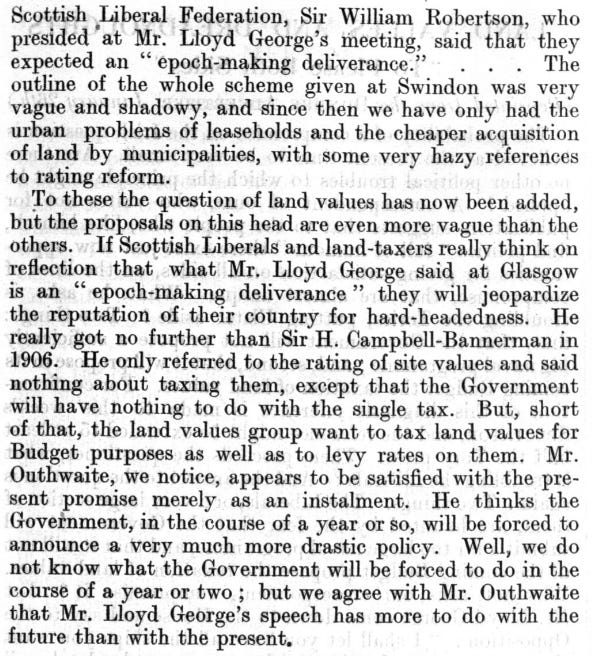

Press reaction to Lloyd George’s speech

“cold and unresponsive as a court of jurors”

“It was a Land Values audience that filled St Andrew’s Hall.”

“a small coterie of mono-maniacs”

“A long suspense was broken. A cheer loud and long rose spontaneously from every corner of the crowded hall.”

“a great step forward which will put heart into the land reform movement all the world over.”

“It was an audience of the preconverted”

“The change came when he mentioned the blessed words site value”

“A singer with a wild and unearthly voice”

“The grey and granite face of Glasgow was transfigured.”

An Address Delivered On February 18, 1884 in the City Hall, Glasgow, Scotland

Henry George: “I have been pointing out the evil. How can it be cured? Well, it cannot be cured by any halfway measures; it cannot be cured by any measures that will be agreeable to your aristocracy.”

It has been said that Henry George’s 1884 Glasgow speech set off the train of events leading to the 1909 Budget. This speech is the origin point of the radicalism featured in these clippings. George’s rhetoric is unsparing:

I draw my blood from these islands. But it so happens this is the only place to which I can trace my ancestry with any certainty. I do not know but that some of my own kindred perhaps today live in Glasgow, and it is from Glasgow men and women some of my blood, at least, is drawn. I am not proud of it. If I were a Glasgow man today I would not be proud of it.

Here you have a great and rich city, and here you have poverty and destitution that would appal a heathen. Right on these streets of yours the very stranger can see sights that could not be seen in any tribe of savages in anything like normal conditions. “Let Glasgow flourish by the preaching of the word” — that is the motto of this great, proud city. What sort of a word is it that here has been preached? Or, let your preaching have been what it may, what is your practice? Are these the fruits of the word — this poverty, this destitution, this vice and degradation? To call this a Christian community is a slander on Christianity.

Low wages, want, vice, degradation — these are not the fruits of Christianity. They come from the ignoring and denial of the vital principles of Christianity.

John Bright, in his installation speech to the Glasgow University in 1883, made a statement, taken from the census of Scotland, in which he declared that 41 families out of every 100 in Glasgow lived in houses having only one room. He further said that 37 per cent beyond this 41 per cent dwelt in houses with only two rooms; thus 78 per cent, or nearly four-fifths of the population, dwelt in houses of one or two rooms. … Now, consider what it implies — this crowding of men, women, and children together. People do not herd that way unless driven by dire want and necessity. These figures imply want and suffering, and brutish degradation, of which every citizen of Glasgow, every Scotsman, should be ashamed.

This city of Glasgow has been crowded with people driven from Ireland and your Highlands where they were living. When I was over in Ireland two years ago I saw the process. I followed some of those red-coated evicting armies, and saw how, at the behest of men who had never set foot in Ireland, the military forces of the Empire were being used to turn out poor people from the cabins and the land on which their fathers had lived from time immemorial. Where were they forced to go? Into cities to obtain work at any price. That great man who has stood on this platform, Michael Davitt, is one of that class.

Thus is your labour market crowded with people who must get work or starve, who cannot employ themselves, who are forced into competition for anything they can get. So with your own people — the people of Scotland. They have been crowded here in the same way. There is the explanation. This is the explanation of the fact that, although during this century, by reason of invention and improved methods, the productive power of labour has increased so wonderfully, wages have not increased at all save where trades unions have been formed and have been able to force them up a little. I have now seen something of Scotland, and let me tell you frankly that what I have seen does not raise my estimate of the Scottish character. Let me tell you frankly — seeing I have been accused of flattering you, and you say you can stand unpleasant truths — I have a good deal more respect for the Irish. The Irish have done some kicking against this infernal system, and you men in Scotland have got it yet to do.

If you were heathens, if you were savages, many of you would be far better off. People would not have to live on oatmeal and potatoes while the streams were flashing with fish and the moors were alive with game.

I have been pointing out the evil. How can it be cured? Well, it cannot be cured by any halfway measures; it cannot be cured by any measures that will be agreeable to your aristocracy.

You cannot cure this deep-seated disease by any such measures as these; you must go to the root, boldly and firmly. Take no stock of those people who preach moderation. Moderation is not what is needed; it is religious indignation. Grasp your thistle. Take this wild beast by the throat. Proclaim the grand truth that every human being born in Scotland has an inalienable and equal right to the soil of Scotland — a right that no law can do away with; a right that comes direct from the Creator, who made earth for humankind; and placed man and woman upon the earth.

Why, I saw in an office today a chart showing the expenses of this nation diagrammed, and, according to that chart, it was nearly all for war, and the cost of war, and preparation for war. ... Why is that expense placed upon you? Because you are governed by a landowning aristocracy. The army is a good place for younger sons. You have been governed by the class that likes to make war, and that finds a profit in making war. With the rule of the people that would cease.

- Henry George, “There is no natural reason for poverty.” - passages from An Address Delivered On February 18, 1884 in the City Hall, Glasgow, Scotland.

The video below examines this speech.

(From Fred Harrison’s Youtube channel.)

“We welcome this long delayed declaration”

Outhwaite “thinks the Government, in the course of a year or so, will be forced to announce a very much more drastic policy. Well, we do not know what the Government will be forced to do in the course of a year or two”

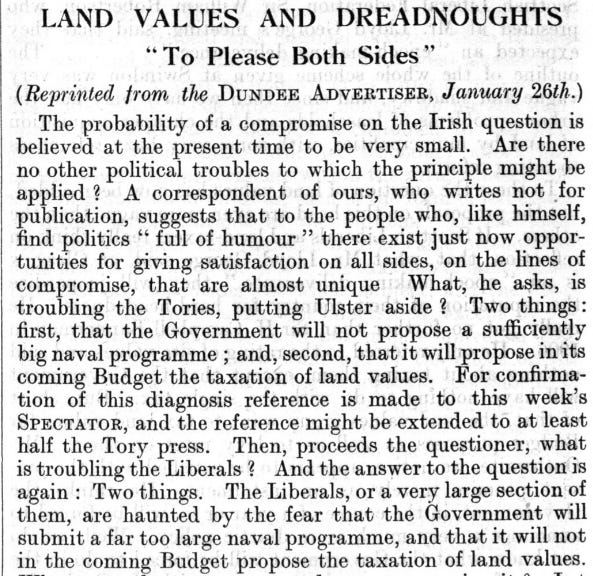

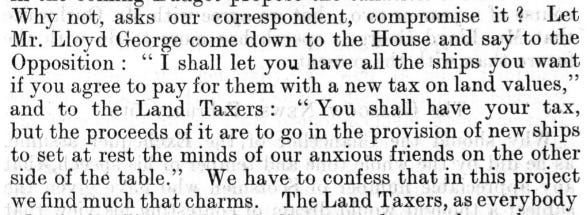

Dreadnoughts v the Single Tax

“What is troubling the Tories, putting Ulster aside? Two things: first, that the Government will not propose a sufficiently big naval programme; and, second, that it will propose in its coming Budget the taxation of land values.”

Land taxes “merely laying it on they will relieve or even cure half the troubles of society”

“the Chancellor of the Exchequer has at last given a foundation for the structure of land reform which is now the policy of the Government.”

Lloyd George: “I am not afraid of Land Values. … I determined, if ever I should have the ball at my feet, I would kick.”

“It is a bigger question than that my brother”

The author of War and Peace

Outhwaite leads the radicals

“We kept silent, and waited for this declaration to come. Now it has come we are determined to make use of it.”

“Don’t look to Parliament, look to yourselves.”

“some section must be tying the hands of the Chancellor”

Mr Raffan: