This postscript is in two parts: the first discusses an important paper I recently came across, the second is a selection of key snips from the series.

"Why should we be beggars with the ballot in our hand?"

Iain McLean (Oxford University), is not the only historian who identifies the land clauses of the 1909 Budget as the immediate cause of the constitutional crisis of 1909-11, but he may be the only one to have delved further into it. In the books that do acknowledge this fact, the land clauses are mentioned only in passing and the great valuation attempt hardly at all, if ever. The combined weight of the remaining causal factors is unimpressive. As we have seen, the most revisionist history, the one most specifically attuned to the radicalism of the age, Dangerfield’s The Strange Death of Liberal England, ignores the the land campaign in the press and in Parliamentary debates, discounts, nay, ridicules Lloyd George - the central figure of the period - and dismisses the principles he argued for in speech after speech. Most damaging to the purpose of his book - the author even ignores prominent liberals at the time declaring that the future of Liberalism depended on or would be destroyed by the Land Campaign.

With Jennifer Nou, McLean wrote a striking article on the politics of the land clauses. The authors assert that the opposition to the land clauses is unprecedented in British Constitutional history. Please read the original, published in 2006 in the British Journal of Political Science. In brief:

("Why should we be beggars with the ballot in our hand?"- Liberal campaign song, General Election of January 1910.)

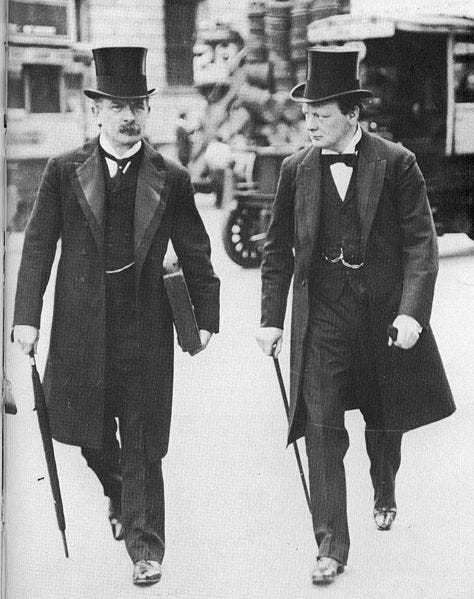

This article is an analytic narrative of an episode in British political history that is well known to historians but curiously overlooked by political scientists, namely the successful obstruction of the elected Liberal governments of the United Kingdom by the unelected House of Lords and the unelected kings Edward VII and George V, between 1906 and 1914. In particular, we draw upon primary archival research along with the secondary literature to examine then Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George's attempt to introduce land value taxation and the factors which led to its demise.

[This] article … shows that the United Kingdom is a paradigm case of a low-n veto player regime, which should mean (but in this case did not) that the elected government gets its way.

Britain is a paradigm low-n veto player regime. Seven features of its modern constitution combine to produce this by ensuring that normally there is no veto player apart from the governing party and its ministers. They are:

1. Sovereignty of parliament.

2. The simple-majority single-ballot system favours the two-party system.

Britain's plurality electoral system will generally produce a single-party majority in the Commons, and hence no rival partisan veto players there.

3. Upper house unelected, and does not obstruct government programme.

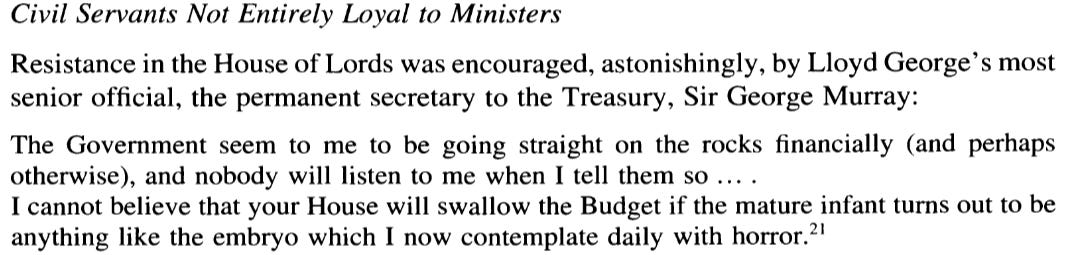

4. Civil service code: loyalty is to ministers.

5. House of Commons control over finance.

6. Monarchy purely ornamental.

7. Courts' subservience to parliament.

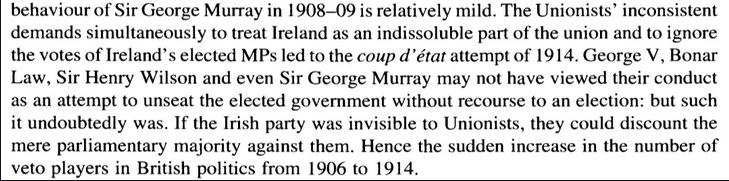

[D]uring the years 1909 to 1914 all seven of these foundational assumptions about the British constitution were violated. So far as we know, these are the only years in British history for which this is true. One would expect extensive political-scientific analysis of this phenomenon; but we have found almost none.

“the Unionists’s attempted coup d’etat has rarely been recognised as such”

“But one looks in vain for any sign of surprise in much of the modern historical literature”

“What, then, is a revolution?”

Stepping back from Nou’s and McLean’s analysis, one is tempted to say that Land Value Taxation was stopped by the “deep state”. In fact, a broader “deep state” theory is posited by another historian, Arno Mayer. His thesis is that the period 1870-1956 was driven as much by counterrevolution as by revolution, and that counterrevolution has been passed over by scholars, resulting in a distorted view of history. Mayer identifies the landed class as the chief counterrevolutionary interest, and that its decline has been exaggerated.

“a nurtured and internally coherent doctrine of innovation”

- Arno J. Mayer, Dynamics of Counterrevolution in Europe, 1870-1956: An Analytic Framework (1971)

The Single Tax v World War One has shown the following:

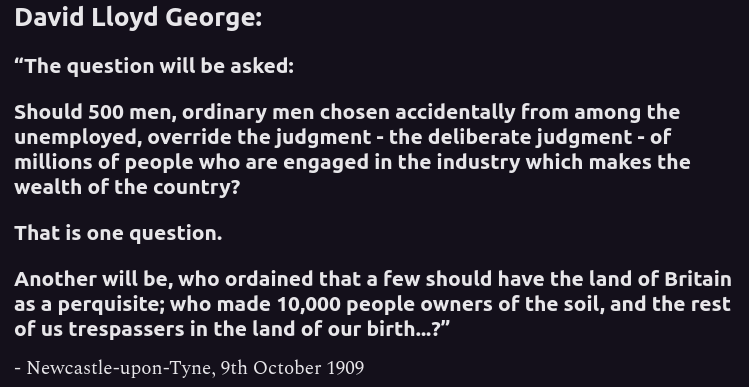

David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, later Prime Minister of the UK, was a Georgist, surely the greatest Georgist politician.

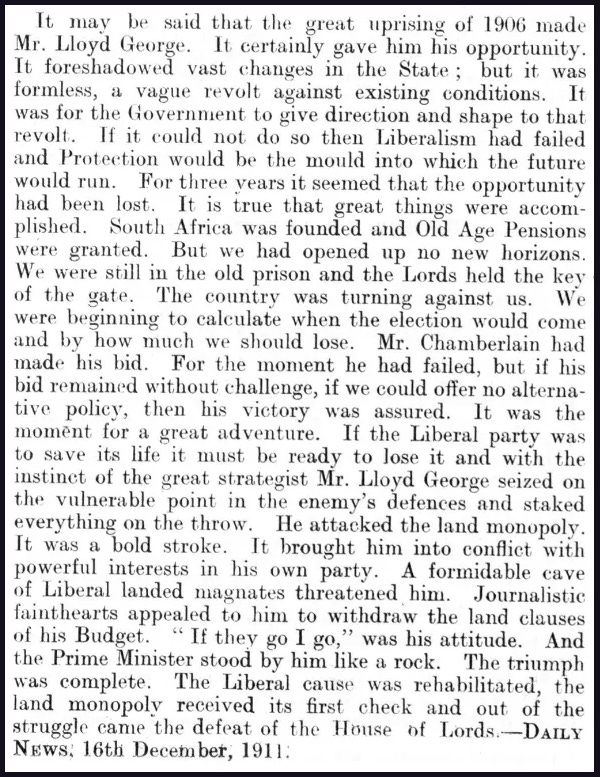

The Budget of 1909, the famous “People’s Budget” was called a “Henry George Budget”. George’s public clashes with the British aristocracy, his widely read and discussed plan to abolish it through government action, were in living memories. This was what made the budget dangerous enough to spark a counterrevolution.

Mayer:

The nationwide land valuation clause alone posed a grave threat to the landed elite. It would facilitate land value taxation, but it could also reveal massive fraud. The last valuation had been the 1086 Doomsday Book.

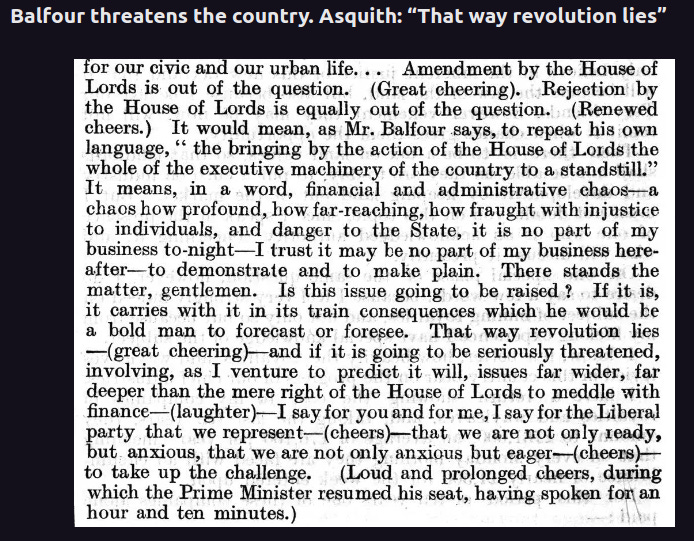

Herbert Asquith, Prime Minister gave several speeches presenting Georgist arguments.

Winston Churchill, as the leader of the Budget League, campaigned up and down the country in support of the land clauses, giving Georgist speeches, including his great critique of State Socialism.

The question of land value taxation was not a new one in Parliament, it had been discussed for decades, with support coming from prominent figures in all parties.

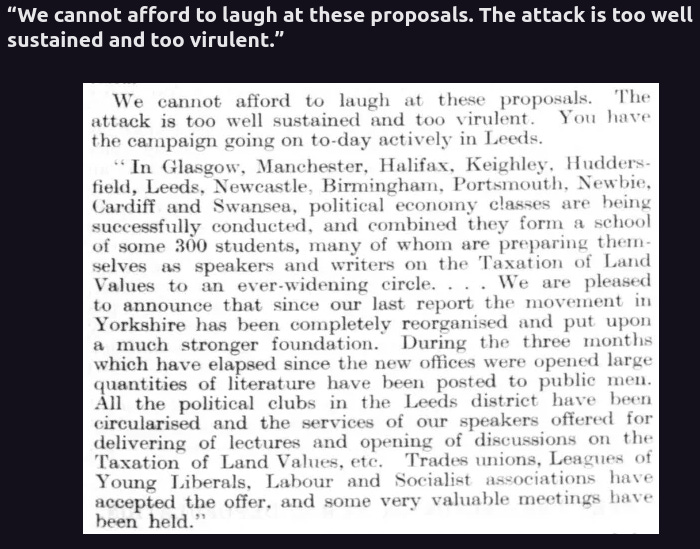

The question of land value taxation was not a new one outside Parliament. The nationwide Land Campaign started in the 1880s by Henry George himself (he toured the UK five times) was, 25 years later - judging by the content presented - growing.

Land Value Taxation was already being adopted in the Empire. Reports from Canada, Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere, were positive.

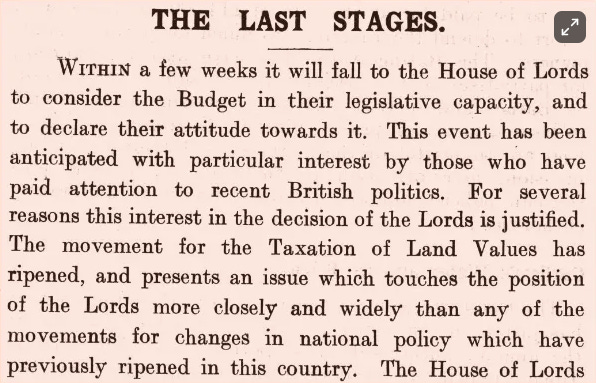

The Lord’s rejection of the Budget and the subsequent constitutional crisis of 1909-1911 was caused primarily if not solely by the Budget’s land clauses. The House of Lords sacrificed its veto to stop them.

Lloyd George repeatedly claimed it was the Valuation they feared.

The years 1911-14 were incredibly contentious both for the Land Campaign and for politics in general. Similar divisions were noticed in other major and soon to be warring nations.

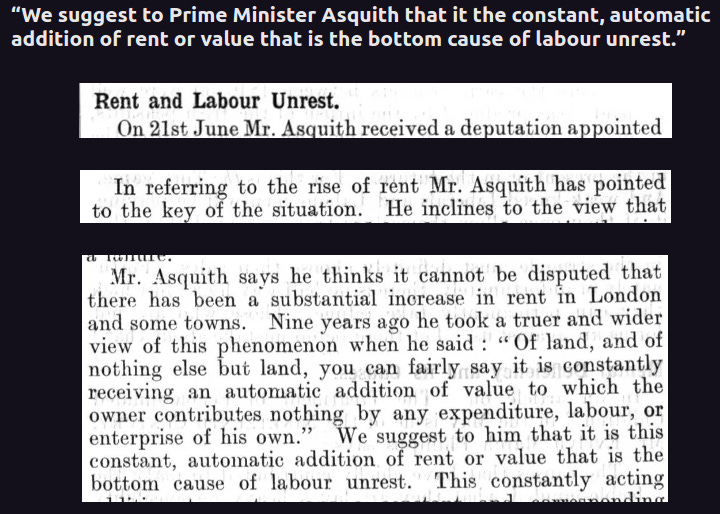

The extraordinary outbreak of strike action from 1910, known as ‘The Great Unrest’, was at least partially driven by a loss of faith in political institutions, specifically due to the government’s failure to deliver promised systemic reform (taxation of land values), due to political resistance at the highest levels of state.

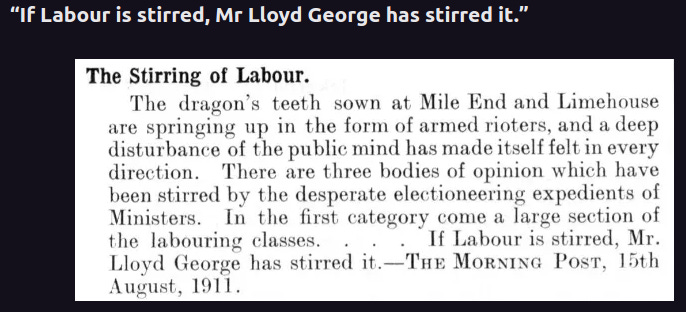

Opinion at the time accused Lloyd George of having stirred up the industrial unrest. The history books make no such link.

The birth of the Welfare State coincides with radical industrial unrest and with the failure to deliver radical reform. Unable to deliver the promised root cuase land reform, the Liberal government - Lloyd George in particular - was forced into extensive palliative measures. Ironic that the creators of the Welfare State knew with conviction it could not work in the long term.

The Marconi scandal of 1912-13 can be viewed primarily as an attempt to prevent the resumption of Lloyd George’s Land Campaign by a smear attack on its leader.

The Irish crisis - which was certainly the most serious of all the issues facing the government - was seen by some as an escalation of the anti-single tax counterrevolution. Ireland was the chosen site for a proxy war against the land campaign.

Industrial unrest did not fizzle out before 1914. In 1914 the big Unions were talking about uniting for a general strike, which would stop the country and could stop any war.

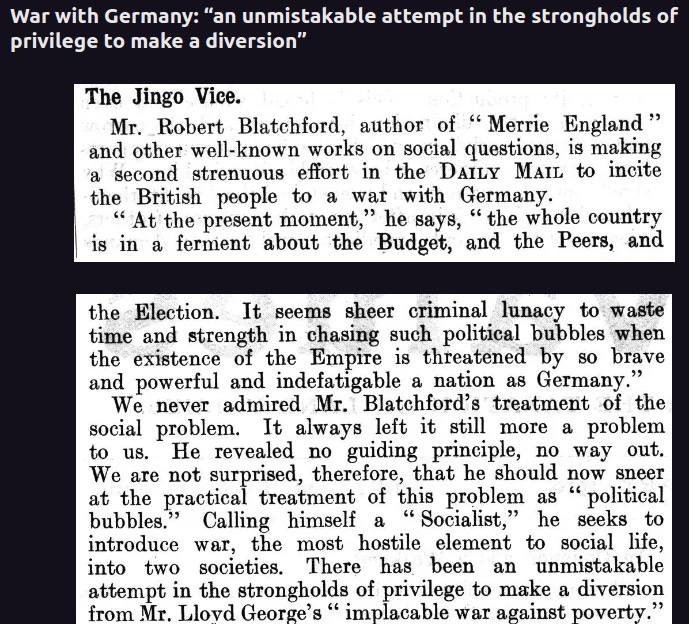

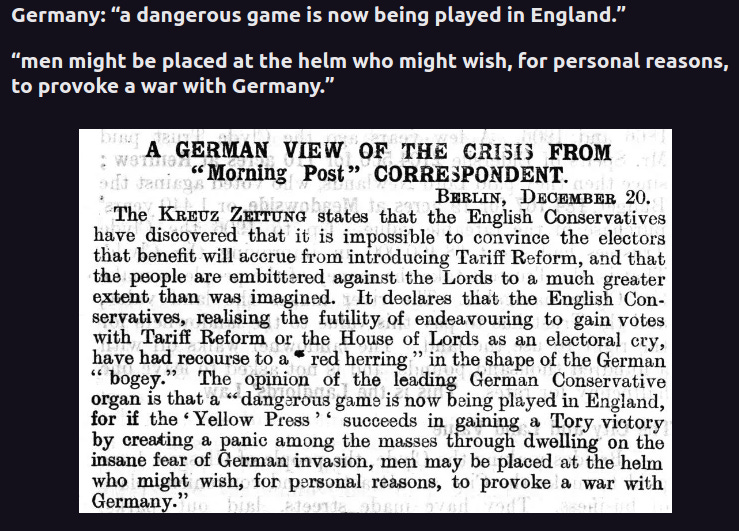

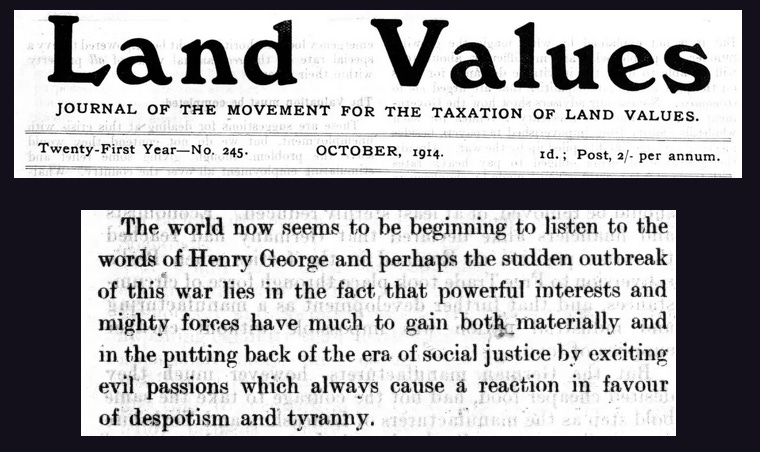

The ramping up of tensions with Germany throughout this period was recognised as tactic to scare the public away from radical domestic reform.

Arno Mayer:

Recent historians of the causes of the Great War have expressed dissatisfaction with the historiography, its failure to identify clear causation. One can understand this given the complexity of the subject, but one is assailed by uncomfortable thoughts: for example, one of the foremost academics in the field, Margaret McMillan, wrote a 600 page book on the origins of the war. It is expressly inclusive yet it makes no mention of the worldwide land reform movement, which for instance, was very strong (as we have seen) in her own country, Canada. Nor does she mention David Lloyd George’s central and dramatic place in that movement, despite being his great granddaughter. McMillan’s nephew, historian Dan Snow is the great great grandson of Lloyd George - he touches the topic, then drops it abruptly, in a tv documentary.

Selections from The Single Tax v World War One

Part 1 May-June 1909

The Budget has just been introduced

Winston Churchill, 1909

Press reaction

Part 2 July-August 1909

The Budget is delayed by Parliamentary debates which run through the summer, into the nights. They all concern the land clauses.

Part 3 September-October 1909

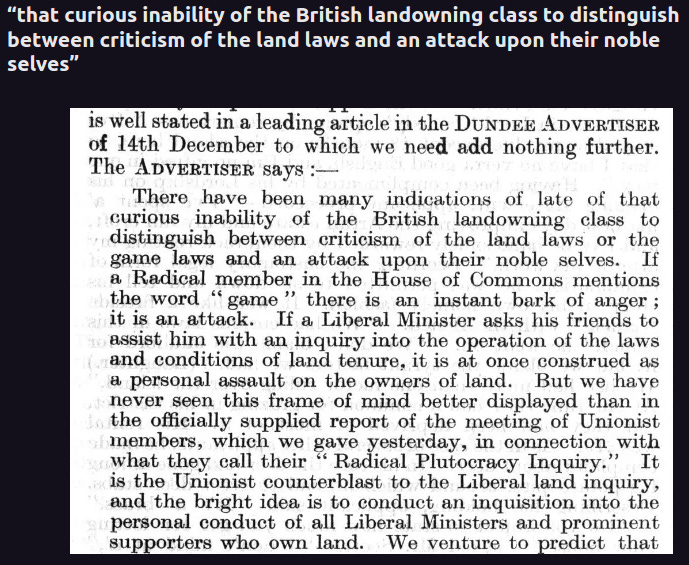

The debate continues to spread from parliament and campaign speeches into the press.

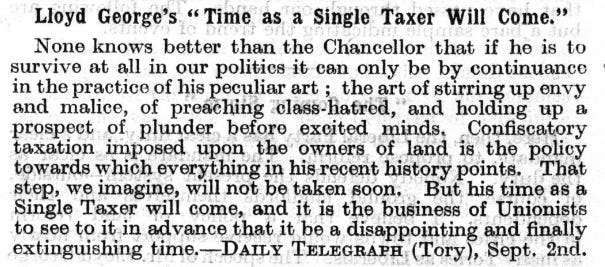

The Telegraph: “the astonishing spectacle of the Prime Minister of England tolerating the advocacy of Henry Georgeism”

Part 4 November-December 1909

The Lords are on the verge of rejecting the Budget.

Part 5 - January-February 1910

The news of the developing crisis spreads, and it develops international dimensions

Lloyd George: “The Sinister Assembly”

Part 6 March-April 1910

Both Land Values and Lloyd George identified the comprehensive national land valuation - the new Doomsday Book - as the true cause of the crisis. Its progress was remarkably swift and although it experienced major delays, it was finally expected to report in 1915

Part 7 May-August 1910

The fact that single tax principles (land value taxation based on site value excluding improvements) were shaping tax policies in the colonies could only have helped give Lloyd George’s fiscal revolution an aura of inevitability.

Part 8 September-December 1910

A race against time.

Part 9 January-July 1911

The Lords and the King have forced two unscheduled general elections and have lost both. The Liberals however, have lost their outright majority. Several new crises blow up and sideline the land agenda.

Part 10 August-December 1911

The counterrevolution has not been halted.

The real cause of the industrial unrest

Part 11 January-March 1912

Throughout this period the grassroots land campaign, the land leagues, are extremely active holding public meetings, organising marches, distributing literature, giving classes. This has been going on for 25 years.

Part 12 April-May 1912

Part 13 June-July 1912

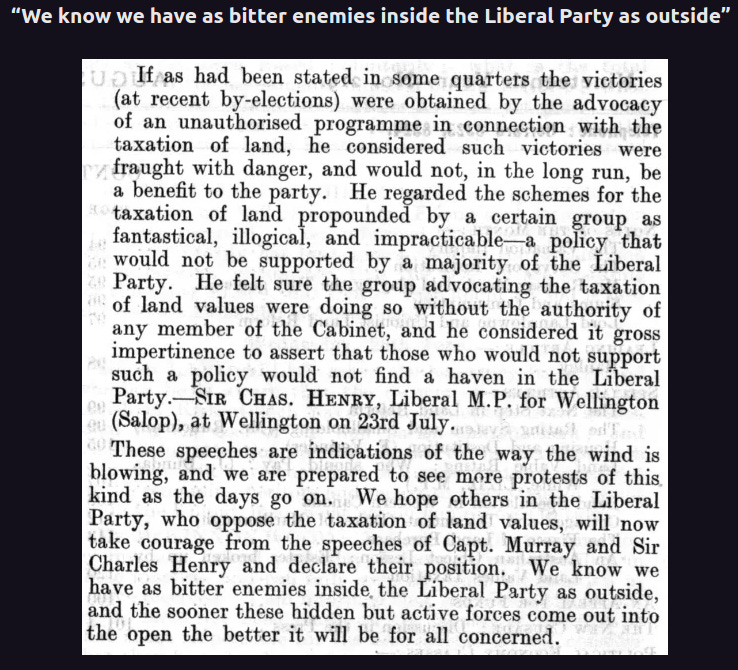

The tensions surrounding the issue appear to make the Liberals hesitate. The land leagues keep applying pressure.

Part 14 August-October 1912

Part 15 November-December 1912

An era of high emotion.

Part 16 January-May 1913

Part 17 June-September 1913

The Valuation and its progress has added a time dynamic to the crisis.

Part 18 October-December 1913

International factors are mentioned with increasing frequency.

Part 19 January-March 1914

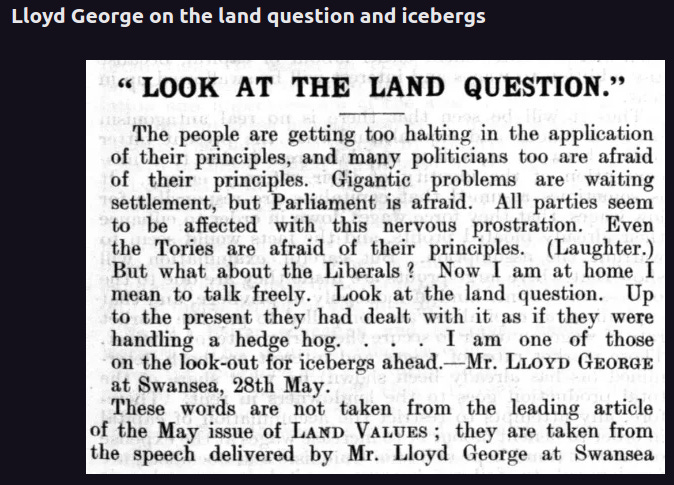

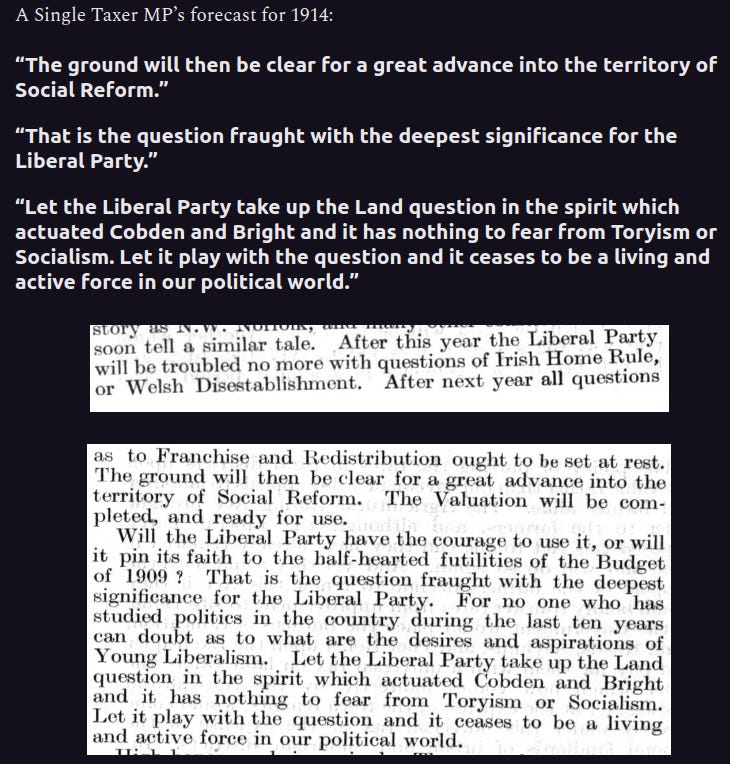

Lloyd George decides to put land value taxation for local government into the 1914 Budget, a major forward step for the Single Tax revolution. More than that, the plan is to make ‘Land’ the central issue of the 1915 general election. It was to be the land for the people election, backed by a national education campaign.

Part 20 April-June 1914

Part 21 July 1914 -

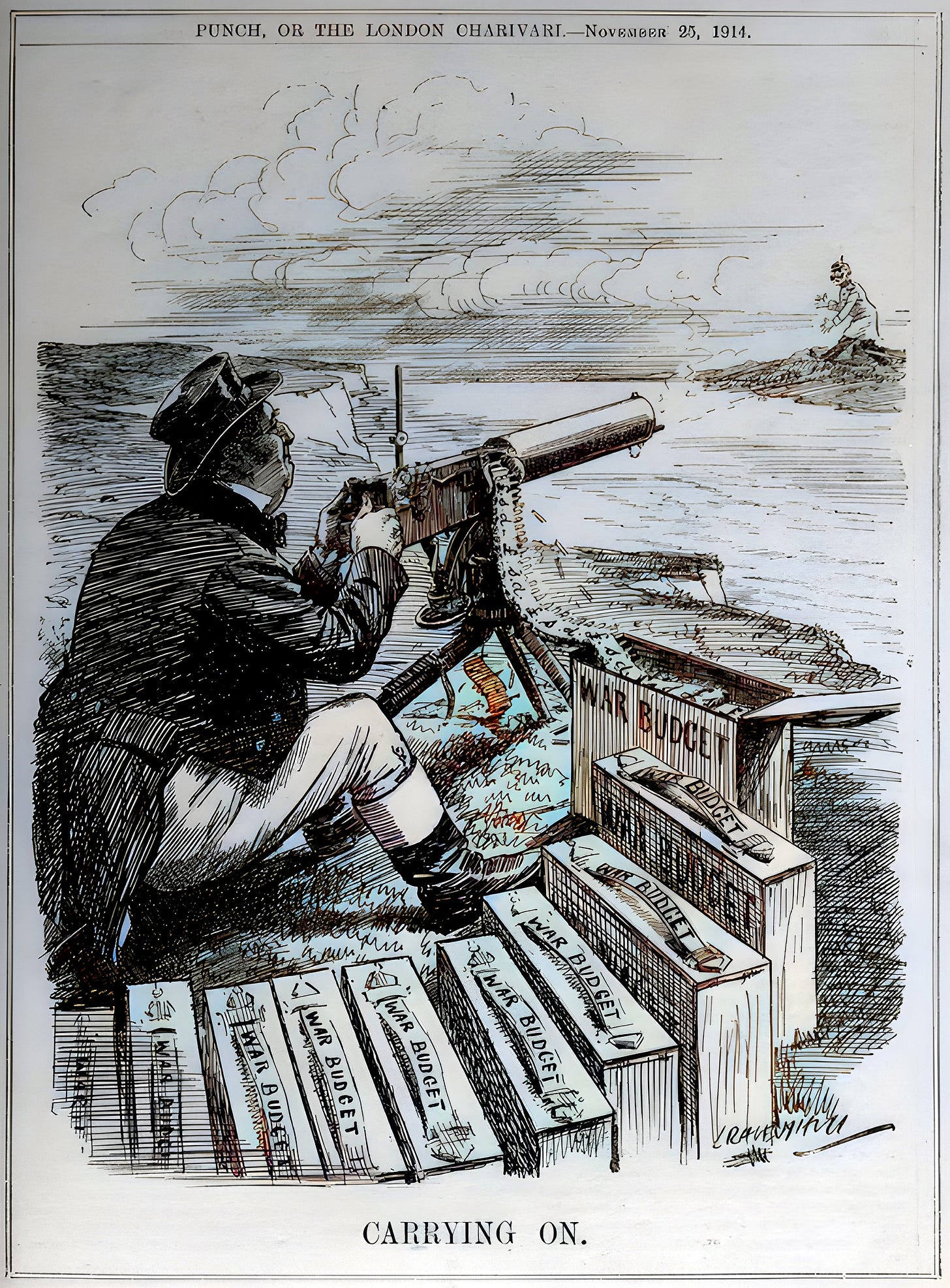

Does this Punch Cartoon connect the 1909 Budget to the decision to go to war in 1914?

there's an article trending on hacker news that is anti LVT and uses a lot of historical claims from the early 20th century to back it up here: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=43353603

your expertise might be invaulable in changing some minds here!

This is fascinating. Henry George was also an inspiration to Sun Yat Sen who wanted to bring the Henry George land tax to China.